In 1903, near the Oseberg Farm in Norway, a farmer discovered a Viking ship built around 820 AD that had been buried for 11 centuries. The ship contained the remains of two women, along with two cows, fifteen horses, six dogs, several ornately carved sleighs and beds, plus tapestries, clothing, and kitchen implements, and—it was discovered in 2007—a small leather pouch containing cannabis seeds.

The find is similar to the Siberian “Ice Princess," a

2500-year-old elaborately tattooed mummy who was found in 1993

similarly appointed with a container of cannabis.

In 2012, archeologists found that hemp had been grown as early as 650-800 AD in Norway, most likely for cordage and sails for ships. However, speculation that the women were carrying cannabis seeds to enable them to cultivate industrial-grade hemp upon their arrival in the next world is disputed by the fact that none of the ropes or textiles found on board the Oseberg ship were made from hemp. “This suggests that the cannabis seeds were intended for ritual use,” writes M. Michael Brady.

One or both of the Viking women, whose ages have been estimated at 50 and 70, may have been a Völva (“priestess” or “seeress”). The older woman, possibly the legendary Queen Åsa, was buried holding a wooden wand or staff, “not only a shamanic implement but also an insignia of their profession. Indeed, the Old Norse term völva has been widely translated to mean a woman ‘wand carrier' or ‘magical staff bearer,’” writes Evelyn C. Rysdyk in her book The Norse Shaman.

"A metal rattle of the sort that a Völva could have used in rituals was found on the ship, fixed to a post topped by a carved animal head and covered with sinuous knot work," writes Brady. "Völvas are presumed to have employed psychoactive substances, as in burning cannabis seeds to induce a trance." In 450 BC Herodotus described Scythian funeral rites where cannabis seeds were thrown onto hot stones and "the Scythians, transported by the vapor, shout aloud."

"Women in ancient Norse society were the ones who primarily practiced shamanism or seiðr,” writes Rysdyk. “A woman who practiced this art was known as a seiðkona or völva. During the Viking Age, practitioners of seiðr were often described as women past their childbearing years [as were both of the women on the ship]. Like their Paleolithic and Neolithic sisters, these women carried the tools of their trade into death….A völva buried in Fyrkat, Denmark was buried with a box containing her talismans or taufr. These included an owl pellet, small bones from birds and animals as well as henbane seeds. When thrown on a fire, henbane seeds can produce a hallucinogenic smoke that gives those who inhale it a sense of flying which may have enhanced the völva’s trance. The völur who were buried in the Oseberg ship were similarly outfitted with a pouch of cannabis seeds for their journey beyond life.”

|

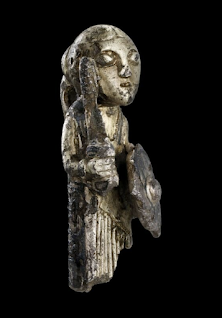

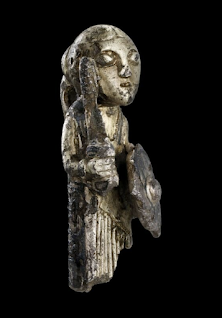

A silver-gilt, 10th-century figurine

found at Harby, Denmark which may

represent Freyja, a Valkyrie,

or a human warrior woman.

|

In A History of the Vikings: Children of Ash and Elm, Neil Price

writes of hallucinogens being found in graves of völva, and the role of

mythical women in Viking lore, such as the Valkyries, female spirits

that guide the dead. "Contrary to the general assumption that the Viking

warrior dead went to Odin in Valhalla, only half of them actually found

a posthumous home there," Price writes. "The remainder traveled to [the

goddess] Freyja in her great hall of Sessrumnir, 'Seat-Room'."

Freyja taught Odin seithr (seiðr), the "highest, most terrible magic." Seithr could "confuse and distract at a fatal moment, or fog the mind with terror. It could strengthen the limbs or disable them, giving someone godlike dexterity, or reduce them to stumbling uselessness. It could make weapons unbreakable or brittle as ice. It was the magic of the battlefield, the farm, the field, the body and the bedroom, and the mind. There was nothing coincidental about its associations with the divinities of war, sex, and intellect."

Other Viking goddesses included Idun, the keeper of the golden apples

that ensured the gods' eternal youth; Eir, a goddess of healing; and

Odin's wife Frigg.