|

| Beauvoir appears in a dream to Lisa Simpson in "Smoke on the Daughter" |

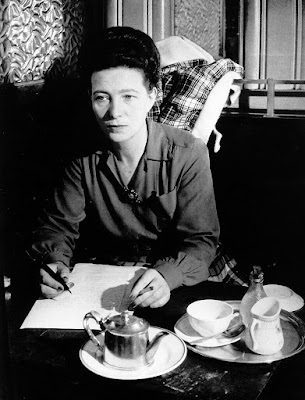

Born in 1908 and educated in a Catholic convent school in Paris, Simone de Beauvoir showed a high intelligence early in life. “Simone thinks like a man,” her father would boast.

She was greatly influenced as a child by Louisa May Alcott's Little Women, and the March sisters. “They were poor and plainly dressed, just as she was. Like her, they were taught that the life of the mind was of higher value than rich food, dress and decoration," wrote Deidre Bair in Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography. George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, where the tragic heroine Maggie Tulliver is “torn between her own happiness and what she perceived as her duty to others,” was also an influence. Both Alcott and Eliot wrote stories in which hashish was mentioned, as did Rudyard Kipling, another author whose books were widely available in French translation at the time.

Beauvoir also witnessed her school friend ZaZa so constrained by her wealthy family's expectations for her to marry well that she mutilated herself in the leg with an axe rather than face another round of staid society parties. Meanwhile, ZaZa's cousin Jacques, a suitor to Simone, was free to visit the bohemian regions of the city, introducing her to a world at a time when, "not many bookish virgins with a particle in their surname got drunk with the hookers and drug addicts at Le Styx," wrote Judith Thurman in the introduction to a 2010 translation of The Second Sex.

A downturn in her family’s finances left Beauvoir with no dowry, knocking her out of the bourgeois marriage market. She studied mathematics, literature/languages, and philosophy at post-secondary schools, aiming towards a teaching career that would support her as a single woman. She scored second place among all French scholars in the agrégation exam in philosophy in 1929; scoring first was the man she would live and/or work with, on and off, for the rest of her life: existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (who was so eccentric he flunked the exam the year before because his answers were too original).

She and Sartre developed theories that became known as existentialism, and in 1945 they and began editing Le Temps modernes, a

monthly review that published authors like Richard Wright, Jean Genet,

and Samuel Beckett. Beauvoir began to write herself: novels like L’Invitée and She Came To Stay, and philosophical treatises like The Ethics of

Ambiguity, in which she argued that out greatest ethical imperative is to create our own life's meaning, while protecting the freedom of others to do the same. She wrote, "A freedom which is interested only in denying others freedom must be denied."

THE HIGH PRIESTESS COMES TO AMERICA

By then known as “The High Priestess of Existentialism,” Beauvoir arrived in New York on January 14, 1947 and was met by a representative of the French cultural services, who took her by taxi to the Hotel Lincoln at Forty-fourth Street and Eighth Avenue. She began a lecture series at the Alliance Française, and “all the women’s colleges wanted her to speak—Vassar, Wellesley, Connecticut College, Smith, Randolph-Axon, Mills. Even Yale, Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania had extended invitations...Where she made her greatest impression was among the students at the women’s colleges, such as at Smith, where her turban, long skirt, regal bearing and incisive questions about women’s education remained strong memories for many women almost forty years later.” [Bair]

Beauvoir was much more interested in spending time in Harlem and Greenwich Village than in the tonier parts of New York. She hung out with black writer Richard Wright and his wife Ellen, and attended a Louis Armstrong Concert at Carnegie Hall with Bernard Wolfe and Mezz Mezzrow, co-authors of Really the Blues about the jazz and drug scene in NYC. Mezzrow was a Jewish clarinetist and pot dealer to Armstrong and other musicians in Harlem. Wolfe was, among other things, Leon Trotsky’s secretary when he was in Mexico with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

|

| Beauvoir with Algren |

“I decided to show her Chicago’s underside,” Algren wrote of his visit with Beauvoir. “I wanted to show her that the U.S.A. was not a nation of prosperous bourgeois, all driving toward ownership of a home in the suburbs and membership in a country club. I wanted to show her the people who drive, just as relentlessly, toward the penitentiary and jail. I introduced her to stickup men, pimps, baggage thieves, whores and heroin addicts….I took her on a tour of the County Jail and showed her the electric chair.”

The night they met, Algren took her to a bar on West Madison Avenue, known as Chicago’s Bowery, where, “No one would turn around if the madwoman of Chaillot came in,” Beauvoir wrote, continuing:

A peroxided blonde handles the cash register. “Everything I know about French literature is thanks to her,” N.A. tells me. “She is very up-to-date.” And as I hesitate to believe him, he asks F. to come and join us for a glass of wine. “How is Malraux doing on his latest novel?” she quickly asks me. “Is there a second volume? And Sartre? Has he finished? Is existentialism still in vogue?” I’m stupefied. This woman spends all her nights supervising this bar, which is also an overnight shelter; her favorite amusements are reading and drugs. It seems she frequently takes drugs and has escaped from prison more than once, and she’s been in and out of the hospital.”

Beauvoir was so upset by the tour the bartender gave her of the squalid rooms where the poor slept that Algren took her back to his place and made love to her, “initially because he wanted to comfort me, then because it was passion.” It was the start of a decades-long love affair and friendship illuminated by the 350 letters Beauvoir wrote to Algren and her novel Les Mandarins, based on their relationship.

In Los Angeles, she stayed with Natasha and Ivan Moffatt, and saw Ivan’s mother, poet/actress and Tokin’ Woman Iris Tree, who Beauvoir thought was "fascinating, beautiful and intelligent." Moffat was an associate producer for Liberty Films, the company George Stevens formed with Frank Capra and William Wyler. Because he liked Beauvoir’s novel All Men Are Mortal, Moffat asked Stevens to consider producing it. He was agreeable, so Moffat wrote a film treatment which Beauvoir liked, and then arranged for Stevens to meet her in the town where he grew up, Lone Pine, where Stevens “wilted in her presence” perhaps "suddenly overawed by Beauvoir’s reputation.” She “characteristically did little to put him at ease.” The film was never made.

Beauvoir crossed the country again by train, and sent a letter from Philadelphia inviting Algren to come to New York, where she checked into the Brevoort Hotel in Greenwich Village, since “true New Yorkers” would no more live in the Times Square district, where her previous hotel had been, “than would true Parisians live in the Champs-Elysées.”THE ROOTS OF “THE SECOND SEX”

In New York, “Beauvoir was puzzled as to why Ellen [Wright], whom she thought an intelligent woman, was content to spend all her time meeting the needs of her husband and child rather than using her considerable talents in a profession of her own,” writes Bair. “She wondered why women choose to devote so much time and energy to serving others when it was so much easier to meet in a bar for drinks and then go on to a restaurant to eat.” Beauvoir “credited this first trip to America with truly opening her eyes to the everyday conditions of women.”

“No man had ever asked me to fetch the coffee or iron the clothes, because I had no intention of doing it for anyone, myself or others,” Beauvoir wrote. “Because I had never felt discrimination among men in my life, I refused to believe that discrimination existed for other women. That view began to change, to crumble, when I was in New York and I saw how intelligent women were embarrassed or ignored when they tried to contribute to a conversation men were having.”

It was with Algren that she first discussed the idea of an article, then a book, about the women’s condition. He had sent her Gunner Myrdal’s book An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, and she asked him to also send her his Nation and Family. She told Algren, “I would like to write a book about woman as important as [Myrdal’s] is about blacks.” She arguably did so, perhaps with the help of some herbal inspiration.

|

| Simone de Beauvoir in Harlem, 1947 |

Beauvoir wrote in her book America Day by Day on May 3, 1947, one of her last days in the U.S.:

As in all big cities, people use a lot of drugs in New York. Cocaine, opium, and heroin have a specialized clientele, but there’s a mild stimulant that’s commonly used, even though it’s illegal—marijuana. Almost everywhere, especially in Harlem (their economic status leads many blacks into illegal drug trafficking), marijuana cigarettes are sold under the counter. Jazz musicians who need to maintain a high level of intensity for nights at a time use it readily. It hasn’t been found to cause any physiological problems; the effect is almost like that of Benzedrine, and this substance seems to be less harmful than alcohol.

Beauvoir says she was “less interested in tasting marijuana itself than in being at one of the gatherings where it’s smoked.” As she describes it, Wolfe took her to a pot party at a fifth-floor room of a well-known, respectable hotel, where she was advised to try smoking herself:

They’ve all smoked already and are feeling high. They offer me a first cigarette: the taste is bitter, unpleasant. I don’t feel anything. They tell me that I haven’t swallowed the smoke; you have to inhale as though you were sucking on a straw. I inhale conscientiously; my throat burns. Everyone is looking at me: “So?” Nothing. The young man in the pajamas carefully gathers up my ashes: no traces must be left. The blonde crushes a perfume-soaked paper against a light bulb and perfumes us one at a time; the smell of marijuana must be masked. The black dancer gives me another cigarette. “They cost a dollar apiece,” he tells me dryly. All right. And I know you have to engage in a complicated strategy to get them. Even if the seller has lots of them in his pockets, he pretends that he must go to the other end of town to find them, so that he can charge more. I apply myself; I do my best. Nothing.

The beautiful brunette is sprawled on the sofa, with her head in her hands, a desperate look on her face. “I feel so happy,” she says. “So insanely happy.” I’m curious about feeling such happiness. I persist—another cigarette. Always nothing….It seems that I ought to feel lifted up by angels: the others are floating, they tell me—they’re flying. The dancer mimes this flight marvelously, and then he does a kind of “slow-motion” number from the movies; he knows how to dance. He look beatific. The brunette repeats, “So insanely happy,” with her eyes full of tears. I try one more time, a last cigarette. All eyes are on me, critical and severe. I feel guilty; my throat is burning. I swallow all the smoke, and no angel bothers to lift me from the earth: I must not be susceptible to marijuana. I turn toward the bottle of bourbon.

I rather wonder if the

brunette Beauvoir wrote about inspired the character in the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s who

is first filled with hilarity and then with tears at a party. Truman Capote’s character Holly Golightly

tries marijuana in his novella on which the movie is based.

|

| Beauvoir being interviewed in 1975 |

According to the book Tete-a-Tete: Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre by Hazel Rowley, Beauvoir found herself passionately kissing Wolfe in front of the Brevoort at four in the morning the night of their cannabinoid encounter. During the few days, “I live in a half-dream; perhaps the marijuana smoke insidiously slipped into my blood,” she wrote.

Back in Paris, dealing with a strange situation with Sartre, who

had taken another mistress, and already missing “my precious beloved Chicago

man” (Algren), Beauvoir “actually took drugs for the first and last time in

her life. Sartre gave her a bottle of the Orthodrine that he popped like

Life-savers, and for almost a week she drugged herself as well” [Bair]. Sartre was a heavy user of a combination of amphetamine and aspirin; Beauvoir saw him

through an experiment he took with mescaline in a hospital setting in 1935. It's interesting that she chose that moment in her life, after her marijuana experience, to try another drug.

Beauvoir, who appeared on the cover of Time magazine two years after her marijuana adventure, was asked by an interviewer in 1975 how it was possible, as she recounted in her memoir, that while writing The Second Sex at the age of 40, she "had not previously perceived the female condition you describe?" She answered that she had not been in a situation to notice the treatment of women, but I've got to wonder if somehow smoking marijuana altered her perception, as it seemed to do for Mark Twain and Pablo Picasso before they made their creative breakthroughs.

After Le Deuxieme Sexe was published in 1949, Beauvoir inscribed first editions of the two-volume set to Wolfe, saying rather cryptically (in translation from French): “For Bernie Wolfe, who has done something or other & made me his great friend….we are friends en poche [in the pocket].” Was the “something or other” Wolfe did for Simone de Beauvoir that she kept in her pocket taking her to a NYC pot party?

No comments:

Post a Comment